| |  | |  | |  | |  | |  | |  | |  | |  | |  | | | | |  | |  | |  | |  | |  |  | Savannah Photo Gallery |

| | |  |  | Savannah Memories |

| | | |  | |  | |  | |  | |

|

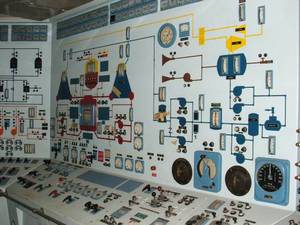

Propulsion

| | Propulsion Control Panel |

Economics of Nuclear Propulsion ...

The Savannah was a demonstration of the technical feasibility of nuclear propulsion for merchant ships and was not expected to be commercially competitive. She was designed to be visually impressive, looking more like a luxury yacht than a bulk cargo vessel, and was equipped with thirty air-conditioned staterooms (each with an individual bath), a dining facility for 100 passengers, a lounge that could double as a movie theater, a veranda, a swimming pool and a library. By many measures, the ship was a success. She performed well at sea, her safety record was impressive, her fuel economy was unsurpassed, and her gleaming white paint was never smudged by exhaust smoke. Even her cargo handling equipment was designed to look good.

From 1965 to 1971, the Maritime Administration leased Savannah to American Export-Isbrandtsen Lines for revenue cargo service. However, Savannah's cargo space was limited to 8,500 tons of freight in 652,000 cubic feet (18,000 m³). Many of her competitors could accommodate several times as much. Her streamlined hull made loading the forward holds laborious, which became a significant disadvantage as ports became more and more automated. Her crew was a third larger than comparable oil-fired ships and received special training after completing all training requirements for conventional maritime licenses. Her operating budget included the maintenance of a separate shore organization for negotiating her port visits and a personalized shipyard facility for completing any needed repairs. No ship with these disadvantages could hope to be commercially successful. Her passenger space was wasted while her cargo capacity was insufficient.

As a result of her design handicaps, Savannah cost approximately $2 million a year more in operating subsidies than a similarly sized Mariner-class ship with a conventional oil-fired steam plant. The Maritime Administration decommissioned her in 1972 to save costs, a decision that made sense when fuel oil cost $20 per ton. In 1974, however, when fuel oil cost $80 per ton, Savannah's operating costs would have been no greater than a conventional cargo ship. (Maintenance and eventual disposal are other issues, of course.) For a short period of time during the 1970s, after the Savannah was decommissioned, she was stored in Galveston, Texas, and was a familiar sight to many travelers on State Highway 87 as they crossed Boliver Roads on the free ferry service operated by the Texas Department of Highways. |

|

|

|